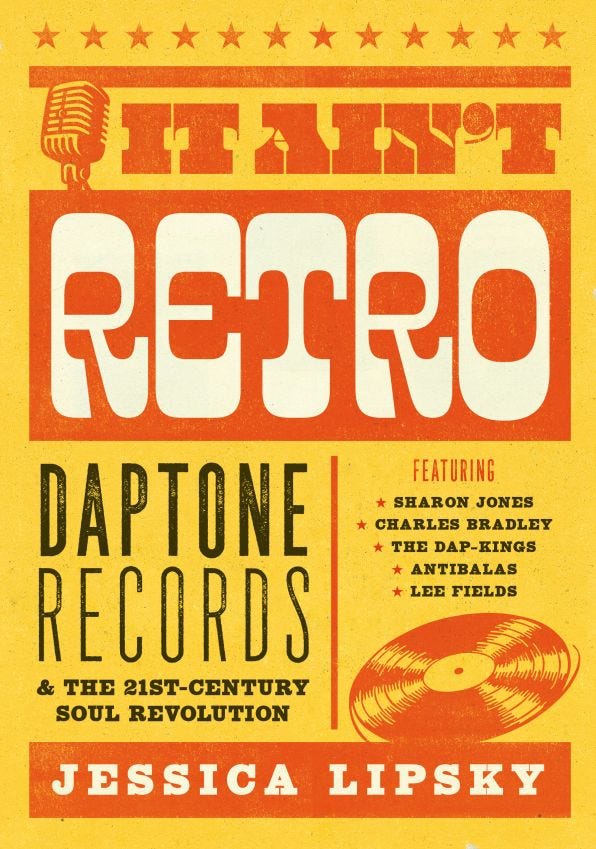

Music Nerd 14: It Ain't Retro

Exclusive interview with author Jessica Lipsky, who chronicles the rise of Daptone Records

MUSIC NERD recently spoke with music journalist Jessica Lipsky about her new book, It Ain’t Retro: Daptone Records & the 21st Century Soul Revolution, out now on UK-based Jawbone Press.

The book chronicles the Brooklyn-based, independent soul and funk record label, which includes Sharon Jones & The Dap-Kings, Charles Bradley, Lee Fields, The Sugarman 3, Budos Band, Menahan Street Band, and other artists. The following interview has been lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

Let’s start with the book title: “It AIN’T Retro.” There’s a punchy combativeness to that title. Do you agree?

A lot of the folks involved in Daptone are sort of anti-establishment. They never gave a fuck if [the music] they put out made money or appealed to popular tastes. They're punks. That defiance is a fun way to draw the eye. It's also a bastardization of a Sharon Jones quote. People would say “it’s retro,” and she would say “there ain't nothing retro about me. I am soul.”

“Punks” is not the first word that comes to mind when I think of the Daptone crew. They dress well for shows and are accomplished musicians.

I don’t think they would call themselves punks, but their rejection of normative tastes and modern recording processes is punk rock. I think about this a lot because I’m interested in subcultures. Is punk the same as it was in 76? The [Daptone] label’s commitment to not deviating from its tastes and following a specific ethos is punk as fuck.

You’ve covered music and culture as a journalist for a long time. What was the impetus to write this book?

I started [writing about music] in high school and never really stopped. I’m 33 now, and I’ve been working as a journalist for about 15 years. I’m super interested in this broad [modern soul] scene as a fan. I had been pitching stories [about the retro soul music scene] for a while, but editors kept saying it was too niche or they’d rather give the story to someone on staff. So I decided to put together a scene study, one that spanned from LA to NY to the UK, and use Daptone as the main character, but it was still too broad and too niche for publishers. So I pivoted to focus on Daptone as a biography, and focus on their contributions to soul music.

How long did you work on this book, and what was your writing and reporting process?

From ideation to shelf it took about three years. I was talking to a friend about my scene study one night, then went back to my AirBnB, a little drunk, and started outlining my book with interesting events and the key players. I went through a list of folks who I knew and wanted to interview, and started to make that happen. I was reporting for about two and a half years. The writing was done during the first months of the pandemic. I had lost my job and that provided some good structure for writing.

Did you hit any snags along the way?

Certainly snags of writer's block, and not being able to secure interviews I needed, and musicians not being on time for interviews, which is hilarious, because during lockdown, I was like, seriously, where are you? What are you doing? But it was so wonderful to learn more about the players behind the music I love so much, and their unique histories. That was really fun.

I was surprised about Charles Bradley. Toward the end of his life, he was pretty ill, so he went to a holistic retreat in Mexico. Nobody knew where he was, and he was not well. That was surprising. The label tried to keep it hush hush. There were so many people in his ear after [he got famous] trying to take advantage of him.

The book dives into Charles Bradley quite a bit, in terms of his traumatic childhood experiences, his reluctance to stop singing James Brown songs and write his own lyrics, and the toll his highly emotional performances took on him.

He had a really hard life. He was functionally illiterate, and he had such a genuine soul that people took advantage of. He is such an interesting character. I looked through decades of press, and there’s this really great article in the New York Times about seeing him in Fort Greene Park, and the reporter said Bradley “made the sky cry,” and that hit me like a ton of bricks. Charles has this depth of pain that is unparalleled. Sharon’s songs were written from the point of view of an empowered woman, but he talked about his brother being murdered. That emotion really resonated with people. His performances were not easy to watch.

Your Author’s note at the beginning of the book describes how your young self disliked pop music and was drawn to Motown, Staxx, and Chess sounds.

The Sunday Night Oldies Show with Tony Sandoval on 98.1 Kiss FM was a huge part of my coming of age. I grew up fascinated with the 60s, which is when my folks grew up. I dove headfirst into it. It just made more sense to me.

Why?

I was moved by the singers, the orchestration, and the tempo. Soul music is just what I wanted to hear. I didn't give a shit about 90s boy bands, I wanted to hear the Temptations. I was probably born in the wrong era. I’ve always been a student of history, and growing up in the Bay Area, counter culture is the culture. 1967-69 is such a big big deal in the Bay Area, and that’s what I grew up with.

You write in the book that you heard the Dap-Kings and you were like “holy shit, this is new.” Can you elaborate?

When I was a freshman in college at [San Francisco ] State, a friend told me KUSF was looking for volunteers. Three months later I had a late night radio show. I was digging through the new music one day and saw Sharon Jones & The Dap-Kings, put it on, and realized oh wow this is brand new and not a reissue. It blew my world wide open.

When Desco Records—the precursor to Daptone—released The Daktaris’ Soul Explosion in 1998, it was presented as a reissue of an unearthed Nigerian LP from the seventies, but it was essentially a hoax.

All the Desco stuff was really about messing with people, and that’s another punk rock thing. Nobody wanted to buy new shit, so why not make it seem like it's older? One of the songs on that album, when read backward, says “[It is all a big hustle.]” It’s pretty funny.

Your description of Daptone on page 8 says “Some overcame illiteracy and homelessness, lifetimes of rejection by record companies, decades working multiple jobs. The others were crate-digging, record-collecting nerds.” How do you think those two disparate groups were able to come together in such creative ways?

Gabe Roth and Phil Lehman [founders of Desco Records, the precursor to Daptone Records] are huge music fans and nerds who wanted to learn more about the kind of music they love. And in so doing, they come into contact with these older performers, who in great measure are Black, and it goes without saying, have been treated much poorly in society due to systemic racism and other things. Sharon Jones was told she was too old and too Black to work in show business. The crate diggers have reverence and respect for the traditions [those artists] grew up in, and a general sense of compassion and camaraderie.

Despite critical success they received after collaborating with UK soul singer Amy Winehouse, the Dap-Kings typically were not topping the charts, but continued to gain fans in a grass-roots way at record stores, noncommercial radio stations and on YouTube.

Gabe [Roth] says Winehouse got them no new fans. But historically speaking, yes, I would posit that it did help a little bit. It got more gigs for the players. If you hear a horn section on a Mark Ronson record, it’s highly likely that it’s three people from Daptone.

You write that Daptone had an ethos to “strike a balance between playing homage and iterating on greatness.” Can you elaborate?

They are certainly playing in a particular style, in a tradition of soul and funk from 1966-72, and they do it perfectly, but they also put their own style and production style onto it. Sharon is like a female modern-day James Brown, so to see an older Black woman with incredible energy and power iterating on that is very powerful and tied to a great tradition.

The book argues that the Dap-Kings mainly earned their audiences and sales through “rough touring” and little pay. Can you talk a bit more about that?

Oh yeah Sharon never really liked being in the studio. She was a performer who wanted to be onstage. But for at least a decade, they played small clubs with 9-10 musicians and were not getting paid well. It's hard to make a living. There's this idea that Daptone is a sort of collective, but it's not. It’s run by two people, and some people get more royalties and song writing credit than others. Some people have been incredibly successful and continue to work with Ronson and produce projects and others are still very much working musicians who struggle.

At the end of the book you say that the core Daptone originators remain “committed punks” putting out soul music that strikes a nerve. What would you say is the real key or secret to their success?

It's good taste and talent, you know. Good taste can be at gut level. Gabe [Roth] may not pick the most virtuosic players, but he picks the ones that have the right vibe. Have good taste in music and talent, and find people who know how to play the way you want them to. That’s how you do it.